|

| The Nuts and Bolts of Life: Willem Kolff and the Invention of the Kidney Machine, by Paul Heiney. |

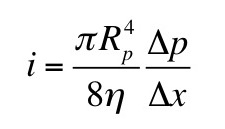

Two compartments, the body fluid and the dialysis fluid, are separated by a membrane that is porous to the small molecules to be removed and impermeable to larger molecules. If such a configuration is maintained long enough, then the concentration of any solute that can pass through the membrane will become the same on both sides.The history of the artificial kidney is fascinating. Paul Heiney describes this story in his book The Nuts and Bolts of Life: Willem Kolff and the Invention of the Kidney Machine.

Willem Kolff…has battled to mend broken bodies by bringing mechanical solutions to medical problems. He built the first ever artificial kidney and a working artificial heart, and helped create the artificial eye. He s the true founder of the bionic age in which all human parts will be replaceable.Heiney’s book is not a scholarly treatise and there is little physics in it, but Kolff’s personal story is captivating. Much of the work to develop the artificial kidney was done during World War II, when Kolff’s homeland, the Netherlands, was occupied by the Nazis. Kolff managed to create the first artificial organ while simultaneously caring for his patients, collaborating with the Dutch resistance, and raising five children. Kolff was a tinkerer in the best sense of the word, and his eccentric personality reminds me of the inventor of the implantable pacemaker, Wilson Greatbatch.

Below are some excepts from the first chapter of The Nuts and Bolts of Life. To learn more about Kolff, see his New York Times obituary.

What might a casual visitor have imagined was happening behind the closed door of Room 12a on the first floor of Kampen Hospital in a remote and rural corner of Holland on the night of 11 September 1945? There was little to suggest a small miracle was taking place; in fact, the sounds that emerged from that room could easily have been mistaken for an organized assault.

The sounds themselves were certainly sinister. There was a rumbling that echoed along the tiled corridors of the small hospital and kept patients on the floor below from their sleep; and the sound of what might be a paddle-steamer thrashing through water. All very curious…

The 67-year-old patient lying in Room 12a would have been oblivious to all this. During the previous week she had suffered high fever, jaundice, inflammation of the gall bladder and kidney failure. Not quite comatose, she could just about respond to shouts or the deliberative infliction of pain. Her skin was pale yellow and the tiny amount of urine she produced was dark brown and cloudy….

Before she was wheeled into Room 12a of Kampen Hospital that night, Sofia Schafstadt’s death was a foregone conclusion. There was no cure for her suffering; her kidneys were failing to cleanse her body of the waste it created in the chemical processes of keeping her alive. She was sinking into a body awash in her own poisons….

But that night was to be like no other night in medical history. The young doctor, Willem Kolff, then aged thirty-four and an internist at Kampen Hospital, brought to a great crescendo his work of much of the previous five years. That night, he connected Sofia Schafstadt to his artificial kidney – a machine born out of his own ingenuity. With it, he believed, for the first time ever he could replicate the function of one of the vital organs with a machine working outside the body…

The machine itself was the size of a sideboard and stood by the patient’s bed. The iron frame carried a large enamel tank containing fluid. Inside this rotated a drum around which was wrapped the unlikely sausage skin through which the patient’s blood flowed. And that, in essence, was it: a machine that could undoubtedly be called a contraption was about to become the world’s first successful artificial kidney…