|

| Drawdown, Edited by Paul Hawken. |

The genesis of Project Drawdown was curiosity, not fear. In 2001 I began asking experts in climate and environmental fields a question: Do we know what we need to do in order to arrest and reverse global warming? I thought they could provide a shopping list. I wanted to know the most effective solutions that were already in place, and the impact they could have if scaled. I also wanted to know the price tag. My contacts replied that such an inventory did not exist, but all agreed it would be a great checklist to have, though creating one was not within their individual expertise. After several years, I stopped asking because it was not within my expertise either.Many solutions are presented in Drawdown, but here I count down the top ten, ranked according to their total atmospheric carbon dioxide reduction, with a brief quote from Drawdown accompanying each.

Then came 2013. Several articles were published that were so alarming that one began to hear whispers of the unthinkable: It was game over. But was that true, or might it possibly be game on? Where did we actually stand? It was then that I decided to create Project Drawdown. In atmospheric terms drawdown is that point in time at which greenhouse gases peak and begin to decline on a year-to-year basis. I decided that the goal of the project would be to identify, measure, and model one hundred substantive solutions to determine how much we could accomplish within three decades towards that end.

10. Rooftop Solar

As households adopt rooftop solar… they transform generation [of electricity] and its ownership, shifting away from utility monopolies and making power production their own.

9. Silvopasture

Silvopasture is… the integration of trees and pasture or forage into a single system for raising livestock… Trees create cooler microclimates and more protective environments, and can moderate water availability. Therein lies the climatic win-win of silvopasture: As it averts further greenhouse emissions from one of the world’s most polluting sectors, it also protects against changes that are now inevitable.

8. Solar Farms

Any scenario for reversing global warming includes a massive ramp-up of solar power by mid-century. It simply makes sense: the sun shines every day, providing a virtually unlimited, clean, and free fuel at a price that never changes. Small, distributed clusters of rooftop panels are the most conspicuous evidence of the renewables revolution powered by solar photovoltaics (PV). The other, less obvious iteration of the PV phenomenon is large-scale arrays of hundreds, thousands, or in some cases millions of panels [solar farms] that achieve generating capacity in the tens or hundreds of megawatts.

7. Family Planning

Increased adoption of reproductive healthcare and family planning is an essential component to achieve the United Nations’ 2015 medium global population projection of 9.7 billion people by 2050. If investment in family planning, particularly in low-income countries, does not materialize, the world’s population could come closer to the high projection, adding another 1 billion people to the planet.

6. Educating Girls

Girls education, it turns out, has a dramatic bearing on global warming. Women with more years of education have fewer, healthier children and actively manage their reproductive health… Synchronizing investments in girls’ education with those in family planning would be complementary and mutually reinforcing. Education is grounded in the belief that every life bubbles with innate potential. When it comes to climate change, nurturing the promise of each girl can shape the future for all.

5. Tropical Forests

In recent decades, tropical forests... have suffered extensive clearing, fragmentation, degradation, and depletion of flora and fauna… One of the dominant storylines of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was the vast loss of forestland. Its restoration and re-wilding could be the twenty-first-century story.

4. Plant-Rich Diet

Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.

3. Reduced Food Waste

Whether on the farm, near the fork, or somewhere in between, efforts to reduce food waste can address emissions and ease pressure on resources of all kinds, while enabling society more effectively to supply future food demand.

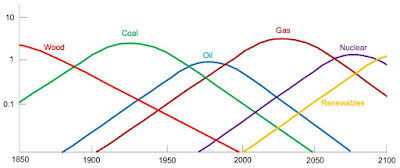

2. Wind Turbines

Ongoing cost reduction will soon make wind energy the least expensive source of installed electricity capacity, perhaps within a decade.

1. Refrigerant Management

As temperatures rise, so does reliance on air conditioners. The use of refrigerators, in kitchens of all sizes and throughout “cold chains” of food production and supply, is seeing similar expansion. As technologies for cooling proliferate, evolution in refrigerants and their management is imperative.

While reading Intermediate Physics for Medicine and Biology, let’s turn up the thermostat a bit during warm days. Between chapters, let’s ditch the hamburger and eat a salad instead (and if you can’t finish it, save the rest for leftovers). Let’s make sure girls in particular are encouraged to read IPMB (or whatever else that will help with their education). And let’s write our congressional representatives and encourage them to support solar and wind energy sources.

If you don’t have the time to read Drawdown, or don’t have easy access to it, then visit the website drawdown.org or watch the videos below, which summarize the plan to reverse global warming.

Climate Solutions 101. Unit 1, Setting the Stage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qT_O2F5zgXc&list=PLwYnpej4pQF7UPnt0nkZEa8sxR9TmWR1B&index=1

Climate Solutions 101. Unit 2, Stopping Climate Change

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bkDherHOymo&list=PLwYnpej4pQF7UPnt0nkZEa8sxR9TmWR1B&index=2

Climate Solutions 101. Unit 3, Reducing Sources

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EiE2DbUOmgc&list=PLwYnpej4pQF7UPnt0nkZEa8sxR9TmWR1B&index=3

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n_ysjDqZlDw&list=PLwYnpej4pQF7UPnt0nkZEa8sxR9TmWR1B&index=4

Climate Solutions 101. Unit 5, Putting It All Together

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t3tZi7aTym8&list=PLwYnpej4pQF7UPnt0nkZEa8sxR9TmWR1B&index=5

Climate Solutions 101. Unit 6, Making It Happen

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xmt1oOUis0E&list=PLwYnpej4pQF7UPnt0nkZEa8sxR9TmWR1B&index=6