Section 16.12

Problem 34 ½. Consider two scenarios.

Scenario 1: N* particles are distributed evenly in a volume V*, so the concentration is C* = N*/V*.

Scenario 2: The volume V* is divided into two noninteracting regions of volume V1 and V2, where V* = V1 + V2. All N* particles are placed in V2. Therefore, the concentration of particles in V1 is C1 = 0, and the concentration in V2 is C2 = N*/V2 = N*/V*[(V1 + V2)/V2] = C*[(V1 + V2)/V2].

Now, examine two cases about how, in a local region, cellular damage, D, relates to the concentration C.

Case 1: Damage is proportional to the concentration. In other words, D = αC, where α is a constant of proportionality.

Case 2: Damage is proportional to the square of the concentration. In other words, D = βC2, where β is another constant of proportionality.

For both cases and both scenarios (a total of four different situations), average the damage over the entire volume V* to get D. Find how D is related to C*.

Stop! To get the most out of this blog post, stop reading and solve this homework problem yourself...

...Okay, so you solved it and now you’re back. Help me explain it to that fellow who didn’t bother to solve it for himself.

Case 1 (damage proportional to concentration)

Scenario 1: The concentration is uniform throughout V*. Averaging the local relation D = αC over V* simply gives D = αC*. The average relationship is the same as the local relationship.Case 2 (damage proportional to concentration squared)

Scenario 2: Locally, D1 = 0 because all the particles are in V2 so C1 = 0. Moreover, D2 = α C2 = αC*[(V1 + V2)/V2]. Now, average the damage over the volume V*. You get D = [V1/(V1 + V2)] (0) + [V2/(V1 + V2)] αC*[(V1 + V2)/V2]. But all those complicated factors cancel out, and you get simply D = αC*. This is the same result as in scenario 1. The average damage is proportional to C*.

Scenario 1: Again, the concentration is uniform throughout V*. So you just get D = βC*2. All that matters is the average concentration, C*.

Scenario 2: Locally, D1 = 0 and D2 = βC22 = βC*2[(V1 + V2)/V2]2. Now average over the volume V*. You get D = βC*2[(V1 + V2)/V2]. If V2 is much less than V1, then D is much greater than βC*2. It is as if the average damage is supercharged by the concentration being, well, concentrated. In this scenario, the average damage depends on both C* and the ratio V1/V2.

This is all interesting, but what does it mean? It means that if you deposit energy locally, then the concentration (or "dose") alone may not tell the whole story. It depends on how the damage depends on the concentration. What is an example of when the damage would be proportional to the square of the concentration? Suppose we are talking about damage to DNA. The concentration might refer to the number of “breaks” in the DNA strand caused by radiation. Now suppose further that DNA has a repair mechanism that can fix breaks as long as they are far apart. That is, as long as they are isolated. But if you get two breaks near each other, then the repair mechanism is overwhelmed and doesn’t work. So, you need two “breaks” close together or you get no damage (in the jargon of radiobiology, you need double-strand breaks instead of just single-strand breaks). The concentration squared tells you something about having two events happen at the same place. You need a “break” to happen at some target spot along the DNA (proportional to the concentration) and then you need another “break” to happen nearby (again, proportional to the concentration), so the probability of getting two breaks near the target spot is proportional to the concentration squared.

Now let’s compare x-rays and alpha particles. Suppose you irradiate tissue so that the energy deposited in the tissue is the same for both. Then, the “dose” (energy per unit mass, analogous to C) is the same in both cases. But the alpha particles (scenario 2) deposit all their energy along a few thin tracks, whereas x-rays (scenario 1) deposit their energy all over the place randomly. You might say: well, for alpha particles the energy has a high density along the path, but everywhere else there is nothing, so on average those effects balance out. That’s true if damage is proportional to concentration (case 1 above). But if damage is proportional to concentration squared (case 2), it’s not true. The average damage caused by alpha particles is more extensive than for x-rays, even if the energy deposited into the tissue (the dose) is the same. The “equivalent dose” (another term for “damage”) is higher for the alpha particles than for the x-rays.

|

| Intermediate Physics for Medicine and Biology. |

Our whole story about DNA repair mechanisms is reasonable and most likely true. But any other mechanism that results in the damage depending on the concentration (or dose) squared would give the same behavior. This result is not limited to DNA repair processes.

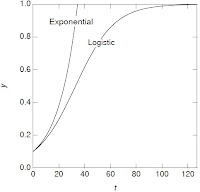

In general, case 1 (damage proportional to concentration) and case 2 (damage proportional to the square of the concentration) are not mutually exclusive. For instance, instead of DNA repair mechanisms being perfect for single-strand breaks and being useless for double-strand breaks, perhaps they are 90% effective for single-strand breaks and only 10% effective for double-strand breaks. In Section 16.9 of IPMB, Russ and I show that cell survival curves typically have two terms, one proportional to the dose and one proportional to the dose squared. At low doses the linear term dominates, but at high doses the quadratic one does.

The goal of toy models is to provide insight. I hope that even though the model in this new homework problem is oversimplified and artificial, it helps you get an intuitive feel for the equivalent dose.