These problems are presented to help someone to become familiar with the analytic volume conduction models of electric potentials and magnetic fields produced by nerve axons or bundles of nerve or muscle fibers developed between 1982 and 1988 in the Living State Physics Group. The problems vary in difficulty, with the very difficult ones marked by a *.The problems are drawn from eight publications I helped write back in the day. If you need copies of these articles so you can solve the problems, just email me: roth@oakland.edu. (Technically the journal owns the copyright, so I won’t link to the pdfs in this blog. 😞)

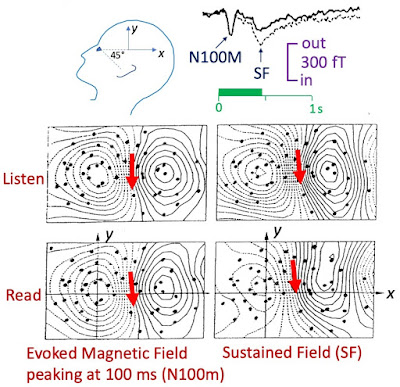

J. K. Woosley, B. J. Roth, and J. P. Wikswo, Jr. (1985) “The Magnetic Field of a Single Axon: A Volume Conductor Model.” Mathematical Biosciences, Volume 75, Pages 1-36.Many of these problems require analyzing Bessel functions and Fourier transforms; I was enamored by those mathematical methods in the 80’s. You can get a hint of what these old homework problems are like by looking at Problem 16 in Chapter 8 of IPMB, where the reader must use these techniques to calculate the magnetic field of a nerve axon.

B. J. Roth and J. P. Wikswo, Jr. (1985) “The Magnetic Field of a Single Axon: A Comparison of Theory and Experiment.” Biophysical Journal, Volume 48, Pages 93-109.

B. J. Roth and J. P. Wikswo, Jr. (1985) “The Electrical Potential and Magnetic Field of an Axon in a Nerve Bundle.” Mathematical Biosciences, Volume 76, Pages 37-57.

B. J. Roth and J. P. Wikswo, Jr. (1986) “A Bidomain Model for the Extracellular Potential and Magnetic Field of Cardiac Tissue.” IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, Volume 33, Pages 467-469.

B. J. Roth and J. P. Wikswo, Jr. (1986) “Electrically Silent Magnetic Fields.” Biophysical Journal, Volume 50, Pages 739-745.

B. J. Roth and F. L. H. Gielen (1987) “A Comparison of Two Models for Calculating the Electrical Potential in Skeletal Muscle.” Annals of Biomedical Engineering, Volume 15, Pages 591-602.

J. P. Wikswo, Jr. and B. J. Roth (1988) “Magnetic Determination of the Spatial Extent of a Single Cortical Current Source: A Theoretical Analysis.” Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, Volume 69, Pages 266-276.

B. J. Roth (1987) “Longitudinal Resistance in Strands of Cardiac Muscle.” Ph.D. Thesis, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee.

Let me give you another example. Problem 10 in this ancient collection is based on the paper by Woosley et al.:

Prove that Eq. (36) and (45) are equal.Equation (36) is the magnetic field of a nerve axon derived using the law of Biot and Savart, and Equation (45) is the magnetic field derived using Ampere’s law. I’ve discussed before in this blog how I could not prove these two equations were equivalent until I found a Wronskian relating Bessel functions.

I’ve also analyzed the IEEE TBME paper in a blog post from 2018.

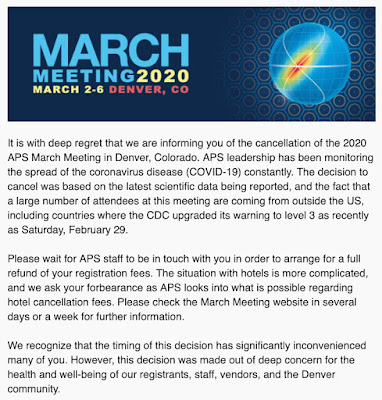

These practice problems are not for the faint of heart. Nevertheless, most of what you need to solve them is in IPMB. If you want to learn some advanced methods in theoretical bioelectricity and biomagnetism, download the practice problems and give them a try. If nothing else, they will provide insight into what I used to work on as a graduate student. Besides, with the coronavirus pandemic holding you in quarantine, what else do you have to do?